| Low-Rent Housing Mandate Q & A What's the goal of the new mandate? The central government is determined to beef up the building of low-rent housing for low-income city dwellers. The goal of the Comments from the State Council on Resolving the Housing Problems of Low-income Urban Families is to “move swiftly to create a sound policy framework that facilitates a multi-channel approach to resolving the problems that urban, low-income families have gaining access to housing, with emphasis on creating a system of affordable rental housing.” Why is the regulation important? It has attached greater importance to the problem of social housing, expanded its coverage, added more financial resources, and linked its implementation by local government officials with their political performance evaluations. Who will supervise? The Ministry of Construction’s Residential Housing and Property Market Administration Division will be split to create a “Housing Access Division” and a “Property Market Administration Division.” The former will be charged with creating the social housing system and drafting and implementing policy, the latter will concentrate on oversight of the property sector. What is the debate? The Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Construction differ over how many low-income families actually need social housing. The former estimated 1.1 million; the latter, 4 million. Also, some scholars think only some of current funds allocated for low-rent housing are in place. Before injecting new money, they say government agencies should tighten funds allocation. Where will the money come from? The State Council proposed four sources of funds: local government budget allocations; land sale profits totaling at least 10 percent of net; income from capital growth in housing provident funds; and central government budget transfers and supplemental funds earmarked to support local government investment in low-rent housing in poor regions of western and central China. Are China's new urban dwellers, some 140 million rural-to-urban migrant workers, eligible for low-rent housing? No. |

By staff reporter Chang Hongxiao

Five years ago, 70-year-old Jia Xilin moved his family into a low-rent, government housing complex in Beijing. It’s a small apartment with three rooms and only 60 square meters of floor space.

Jia’s family is one of about 400 in the apartment complex, which was the first, large-scale, low-rent housing development built by Beijing municipal authorities.

They are the lucky ones. Affordable housing is quite rare in the capital city. Indeed, rent-controlled accommodations are available for only about one out of every 300 families in Beijing, a city with an estimated 200,000 low-income households.

Farmers at a construction site in Zhengzhou, Henan province. Behind them is an upscale apartment complex.

But soon, a lot more affordable, rent-controlled homes are expected to be built in Beijing and other cities across China. The State Council, China’s cabinet, is pushing for change with a newly released mandate that calls for “establishing a complete social housing system” – a system that could cost hundreds of billions of yuan.

Questions about the government’s responsibility toward urban housing access have been around for years. Answers have not been clear-cut. The new mandate, however, hopes to settle the issues by addressing dilemmas over home affordability faced by many Chinese families.

“From now on, the government at every level will have to come up with ways and means to guarantee that everyone has access to housing,” said Lin Jiabin, a deputy director of the State Council Development Research Center (SCDRC) who contributed to research leading to the new regulation. “I think that’s something everyone would agree on.”

The document was made public on the government’s official Web site August 13. Lin told Caijing the document is significant in that it clearly shows that the government accepts responsibility for ensuring at least basic access to decent housing for low-income urban families, and takes steps toward establishing a policy framework for social housing guarantees.

This is no small change. The document represents a major turning-point in Chinese housing policy and reform for the housing system. The government will have greater responsibility to guarantee access to housing, which will be treated as a public service similar to compulsory education and basic health care. Governments at various levels will be required to invest in housing and exercise better oversight of the housing market.

The release of the new document also reveals that the function of government in the housing market is changing. Before, different levels of government would make efforts to stabilize housing prices and attempt to ensure reasonable housing for low-income groups. But outcomes were often poor.

Now, the government finds its burden lighter. Guaranteeing housing access for the poor has been separated from a responsibility to encourage growth in the housing sector. Apart from preventing speculation, the government will no longer be expected to interfere much in the housing prices.

Reliable sources told Caijing that, while this housing guarantee system is being established, the Ministry of Construction’s Residential Housing and Property Market Administration Division will be split to create a “Housing Access Division” and a “Property Market Administration Division.” The former will be charged with creating the social housing system and drafting and implementing policy in this regard. The latter will concentrate on oversight of the property sector.

As Lin sees it, “trying to use housing price controls to help low-income families get access to housing is a pointless exercise. Experience has shown that some of these policies not only failed to achieve the desired outcome, but they actually ended up making matters worse in the housing market.”

Long Guoqiang, deputy director of SCDRC’s Foreign Economic Relations Department, said in an interview with Caijing that the government has two main functions in terms of the housing issue. One is to arrange for social housing. Here, the government has to get involved in housing provision. The other is regulating the housing market -- making sure players stick to the rules of the game. In this arena, the government only draws up a clear set of rules but enforces them with a strict hand.

More Low-Rent Housing

According to a traditional Chinese saying, “Food, clothes, shelter and mobility are the fundamentals of the people’s livelihoods.” Most countries regard access to housing as a “basic right” and make it a major facet of public policy. The belief is that decent housing for low-income families can do much to settle social problems.

China had a planned economy for a long time, with urban housing planned by the government, assigned by the work unit. This collective economy created a general housing shortage.

In the early years of housing reform in 1998, China’s old welfare housing allocation system collapsed. A new goal of monetized housing allocations was proposed. At the time, officials envisioned a new national housing supply system with three layers. First, people with high incomes would buy or rent commercial housing. Affordable or so-called “budget” housing would be made available for sale to middle or low-income households. And rent-controlled housing would be available for the poorest. Architects of this system hoped it would satisfy the bulk of housing demand. It was against this background that a provision for budget housing, the second tier, became the central plank of a national housing supply system.

Every year since 2004, nationwide housing prices have climbed apace with China’s growing economy. Prices have risen for a longer period, and more rapidly, in major metropolises such as Beijing and Shanghai. Yet, construction of rent-controlled housing has been slow. And due to improper planning decisions, the rich wound up buying much of the available budget housing. Many low-income families who were supposed to benefit from the housing system were, in fact, excluded from access to rent-controlled housing and unable to buy budget housing.

The commercial market has developed quite rapidly since the launch of housing reform, and higher-income families have been able to buy their homes. But the more than 20 percent of all urban households nationwide in the low-income bracket have found it extremely difficult to buy homes of their own. The government has been left with no choice but to guarantee housing to middle- and low-income households by interfering with the market. That means, on the one hand, increasing investment in the building of rent-controlled homes on one hand while, on the other, working to regulate and improve the supply of budget housing.

That’s exactly what the State Council’s new document set out to accomplish. Low-renting house has become a future focus for national housing policy. Building on this foundation, the government adopted a multi-channel approach to create a system of affordable rentals.

The document is quite clear. From now on, low-income families will get rent-controlled accommodations. Families with slightly higher but still low incomes can buy budget housing, while households with middle-to-high incomes are expected to buy what is known as “double-restriction housing” – restricted by housing type with price controls -- or purely commercial housing.

Zhao Luxing, director of the Office of the Ministry of Construction’s Policy Research Office, told Caijing that the main thrust of the policy adjustment was to extend the reach of access to rent-controlled housing beyond the poorest families to those with low incomes and housing problems, and to limit access to budget housing so that it remains available to low income households but excludes the middle-income bracket.

Lu Qin, an Institute of Urban Construction researcher at the China Academy of Urban Planning and Design, said this will reduce access to budget housing. And he said “it is not at all unlikely” that budget housing will be phased out entirely.

Other academics think the marked gaps between different regions of the country make it difficult to discuss the situation in various locales and to talk about phasing out budget housing at this time.

“It’s still too early,” Zhang Yuanduan, deputy chair of the China Real Estate and Housing Research Association. He thinks groups targeted for help through rent control and budget housing provisions are not the same. Budget housing is designed to help low-income households “with some level of ability to pay,” whereas rent-controlled homes are “for renting to the lowest-income households who lack the ability to pay.” For this reason, Zhang thinks budget housing will not be phased out.

Where Is the Money?

For the Chinese government, it’s an immense and long-term policy commitment to guarantee affordable housing for low-income families. The new mandate set out a clear timetable, requiring that, by 2010, access to low-rent housing nationwide would be extended from covering only “the lowest income households with housing difficulties” to also include “low-income households with housing difficulties.”

Of course, such a huge expansion of coverage will require a massive amount of investment.

The Ministry of Construction estimates that, across China, some 4 million households are eligible for income supplement welfare. These families have average living accommodation spaces of less than 10 square meters per capita, and are called “double-hardship” households, meaning households with housing difficulties and small income.

Providing low-rent housing for these households alone would require the central government to spend tens of billions of yuan. When projected local government contributions are also figured in, the project’s total cost would be close to 100 billion yuan.

Lin at SCDRC has come up with three potential figures for the investment required. Calculating the costs using three sets of parameters, he found that in the “lowest bracket” project – in which low-rent housing would be available to 6 percent of permanent, urban households on low incomes and 10 percent of migrant populations -- the required investment would be more than 268 billion yuan. His “medium” scenario would extend to 10 percent of the settled, low-income population and 20 percent of migrants, requiring more than 428 billion yuan. The “highest case” envisions coverage for 14 percent of permanent residents and 40 percent of migrant households at a cost of nearly 700 billion yuan.

A basis for Lin’s scenarios is that the government would provide housing for 30 percent of low-income families. The other 70 percent would need other forms of subsidies -- a daunting task that would test the government’s determination as well as its wallet.

That’s why Lin proposes a step-by-step policy. For the first five years, he wants low-rent housing access to be restricted to “lowest bracket” groups. That would require an average annual investment of 50 billion yuan. Afterward, for the next five years, coverage would be extended to households in the “medium” groups. After another 10 years, those in the “highest” bracket would be included.

But money would be hard to find even under Lin’s least expensive scenario. The State Council document proposes four, possible sources of investment funds for low-rent housing: local government budget allocations; land sale profits totaling at least 10 percent of net; income from capital growth in housing provident funds; and central government budget transfers and supplemental funds earmarked to support local government investment in low-rent housing in poor regions of western and central China.

Three of these four sources already exist. The only new investment would be a central government budget transfer to western and central regions. The other three sources would expand as needed. For example, the percentage of profit from land sales to be used on low-rent housing would rise to 10 from 5 percent. Housing provident funds would earmark all earnings on capital growth for low-rent housing, rather than spending these earnings on housing merely “as a priority.”

The central government must inject the money. But the Ministry of Finance (MOF) and the Ministry of Construction disagree over the right amount. One insider told Caijing the construction ministry wants the central government to only create policies and let local governments come up with the money. The finance ministry, however, thinks that since there are no accurate estimates of low-income households with housing difficulties, the actual numbers may be lower than many construction ministry officials think.

Chen Yifang, director of the Land and Housing Office, under the finance ministry’s Policy and Program Department, says that according to a typical-case survey conducted by MOF and other ministries in 2005, China has some 1.1 million “low-income households with housing difficulties” (“double-hardship” households). This is a far cry from the construction ministry’s estimate of 4 million households. The reason for the disparity, in MOF’s view, is that many low income families in cities do not experience housing difficulties.

One expert who spoke with Caijing said social housing guarantees should be the joint responsibility of central and local governments, and that the financial burden should be shared. Since housing is not something that can be relocated, it is very much like a regional public service, and local government should bear some responsibility for meeting building costs. This expert also thinks it would be reasonable for central and local governments to split the cost of building low-rent housing 50-50.

From Policy to Practice

The State Council added teeth to new document by making housing access for low income households a performance indicator for local government officials. This has been one of Beijing’s most effective means for ensuring local authorities govern in line with national policy goals. However, given fiscal limitations, many aspects of the affordable housing policy will not be easy to implement.

One lesson the government should pay close attention to is that funding for affordable housing isn’t working effectively under the current fiscal framework. MOF’s Chen Yifang said the main sticking point holding back low-rent house construction is not a shortage of funds, but rather questions about how to track its usage and increase efficiency.

For example, in the case of profits from housing provident funds, figures from the construction ministry show nationwide withdrawals of such profits were some 10 billion yuan in 2006. But only 2 billion yuan was actually spent on building low-rent housing. The rest of the money stayed in the housing provident fund management centers, or with local finance departments. As for the money from land-sale profits, only 300 million yuan was allocated out of the 13.5 billion yuan that should have been available nationwide for house-building at the 5 percent rate.

Thus, Chen believes the crux of the solution is to make the current funding mechanisms for rent-controlled housing work properly, not asking the central government to invest more money.

Caijing has learned that the new mandate was drafted by the Ministry of Construction together with the SCDRC. During the consultation phase, when opinions from other ministries were sought, MOF offered several views about specific issues in the policy. These views ran to more pages than the actual policy document itself. It seems clear that MOF wants to make sure that current funding policies are fully implemented and that government money that’s already available is used more effectively.

There are perhaps deeper systemic reasons for these problems. Under the current land and finance systems, land sales operate like a “second budget” for local governments. In the past, money from land sales was not included in budget calculations, and it was one of the main funding sources used by local governments for industrial development and urban expansion. Obviously, under the present method of assessing local government performance, they are unlikely to voluntarily start spending this money to build low-rent, public housing.

The other funding source -- housing provident funds – is controlled by agencies under local government departments. Fund management is lax, and there is insufficient public oversight of how the funds are managed or used. Also, there are a number of practical barriers. Fund managers work exclusively for the depositors who are the sole owners of the money in housing provident funds. Any capital gains earnings should, of course, go to the depositors. To say the least, it’s an imposition for the government to compel funds to spend these profits on low-rent housing.

The provident funds mechanism prompted concerns about what would happen if changes are not made to the fiscal system and the method for evaluating local government performance. Local governments may not agree with or implement the new housing policy. Will local governments render the policy impotent? If that happens, what further measures should the central government take to address the problem?

An even more profound problem is China’s army of more than 140 million rural-to-urban migrant workers. These are people who spend at least six months of every year living in cities and towns. Will their housing needs be covered by the new policy? This seems to be a problem that central government agencies are not prepared to address. The new policy sets out some requirements in principle for migrants, but they are not easy to implement in practice. This is another major challenge for the social housing system.

The question is, in fact, related to deeper issues of reform to China’s system of land ownership. Li Tie, director of the Small Town Development Research Center, said farmers who rent rooms to migrant workers near cities and towns could help reduce costs for local governments that implement the new policy. This could be a win-win arrangement. Currently, many rural migrants rent from these suburban farmers. Others live in temporary shacks near their jobs. Some have even purchased “semi-owned” housing, which are built on collective land near towns but having no real legal status.

Li thinks that since the central government’s current Land Management Law does not allow farmers to develop property on collectively owned village land, “semi-owned” housing in suburban areas is illegal, and the de-facto low-rent housing provided by farmers can’t function well.

China’s migrant workers “are, statistically, already part of the urban population,” Li said. “Yet, for the most part, local governments are not providing them with public services such as education, health care or social housing.

“Since we are now looking to improve the provision of affordable social housing,” he said, “why can’t we have some innovations to the system and use the housing provided by suburban farmers, even the ‘semi-owned’ housing, to guarantee migrant workers have access to decent housing?”

1 yuan = 13 U.S. cents

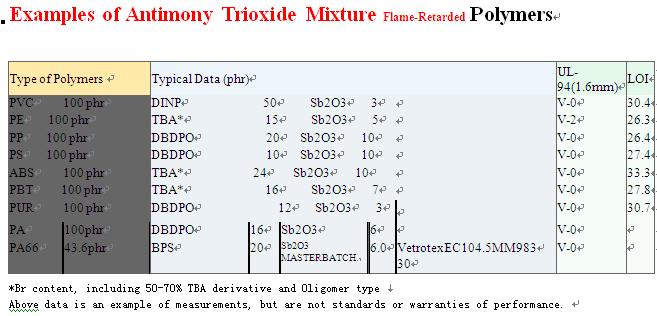

We can supply any quantity and any kind of Antimony products and fire retardant from stock.would you please inform us how many you need and your target price, then we will confirm ASAP. We are sincerely hope to do business with you and establish long term business relationship with your respectable company.

Look forward to hearing from you soon.

Best regards,

Sam Xu

MSN: xubiao_1996@hotmail.com

GMAIL: samjiefu@gmail.com

SKPYE:jiefu1996

Fire retardant masterbatch

0 comment:

Post a Comment